In this article:

Overview

WHO-UNICEF recommendations

Can all women breastfeed?

How do I start breastfeeding?

How do I get my baby to latch on?

What is the let-down reflex?

What is the best position for breastfeeding?

Does breastfeeding hurt?

How do I know my baby is getting enough milk?

Should I breastfeed on demand?

What is a blocked milk duct?

What are mastitis and breast abscess?

How do I express breast milk?

Can I breastfeed with twins or more?

Can I breastfeed if my baby is ill?

What is jaundice?

Is it worth breastfeeding just for a few days?

Doesn't breastfeeding prevent the father from sharing in our baby's care?

Can I breastfeed in public?

Do I need a special diet when breastfeeding?

Can I breastfeed if I am unwell?

Can I breastfeed if I have HIV?

Can I breastfeed if I have hepatitis B?

Does any prescribed medication affect breastfeeding?

Can I use recreational drugs when breastfeeding?

Can I smoke when breastfeeding?

Can I drink alcohol if breastfeeding?

Who can advise me on my worries about breastfeeding?

Can I breastfeed whilst pregnant?

When should I stop breastfeeding?

Can I go back to breastfeeding if I have stopped?

Overview

WHO-UNICEF recommendations

Can all women breastfeed?

How do I start breastfeeding?

How do I get my baby to latch on?

What is the let-down reflex?

What is the best position for breastfeeding?

Does breastfeeding hurt?

How do I know my baby is getting enough milk?

Should I breastfeed on demand?

What is a blocked milk duct?

What are mastitis and breast abscess?

How do I express breast milk?

Can I breastfeed with twins or more?

Can I breastfeed if my baby is ill?

What is jaundice?

Is it worth breastfeeding just for a few days?

Doesn't breastfeeding prevent the father from sharing in our baby's care?

Can I breastfeed in public?

Do I need a special diet when breastfeeding?

Can I breastfeed if I am unwell?

Can I breastfeed if I have HIV?

Can I breastfeed if I have hepatitis B?

Does any prescribed medication affect breastfeeding?

Can I use recreational drugs when breastfeeding?

Can I smoke when breastfeeding?

Can I drink alcohol if breastfeeding?

Who can advise me on my worries about breastfeeding?

Can I breastfeed whilst pregnant?

When should I stop breastfeeding?

Can I go back to breastfeeding if I have stopped?

Overview

Breastfeeding is one of the most effective ways to ensure child health and survival. However, nearly 2 out of 3 infants are not exclusively breastfed for the recommended 6 months—a rate that has not improved in 2 decades.Breastmilk is the ideal food for infants. It is safe, clean and contains antibodies which help protect against many common childhood illnesses. Breastmilk provides all the energy and nutrients that the infant needs for the first months of life, and it continues to provide up to half or more of a child’s nutritional needs during the second half of the first year, and up to one third during the second year of life.

Breastfed children perform better on intelligence tests, are less likely to be overweight or obese (see separate article childhood obesity) and are also less prone to diabetes later in life. Women who breastfeed also have a reduced risk of breast and ovarian cancers.

Breastfeeding also nurtures national economies. Increased rates of breastfeeding can improve a country’s prosperity by lowering healthcare costs and producing stronger, more able workforces.

Inappropriate marketing of breast-milk substitutes continues to undermine efforts to improve breastfeeding rates and duration worldwide.

WHO-UNICEF recommendations

WHO and UNICEF recommend that children initiate breastfeeding within the first hour of birth and be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life – meaning no other foods or liquids are provided, including water.Infants should be breastfed on demand – that is as often as the child wants, day and night. No bottles, teats or pacifiers should be used.

From the age of 6 months, children should begin eating safe and adequate complementary foods while continuing to breastfeed for up to 2 years and beyond.

Although a vital part of a child's healthy growth and development, breastfeeding is not a one woman job. It requires encouragement and support from skilled counsellors, family members, health care providers, employers, policymakers and others. See separate article on World Breastfeeding Week.

Mothers need support both to start and to sustain breastfeeding. Thus, the WHO advocates skilled breastfeeding counselling services and in partnership with UNICEF created the Global Breastfeeding Collective to rally political, legal, financial, and public support for breastfeeding.

Can all women breastfeed?

Most women are physically able to breastfeed. It is rare for a mother to be physically unable to breastfeed. It doesn't matter whether you have very small or large breasts, or if you have inverted nipples. Most of the larger breast is made of fat and the milk-producing (mammary) parts are very small. Your breast tissue is designed to make enough breast milk for your baby. If you have twins, it is usually possible to make enough milk for both babies. |

| Motherhood painting depicting woman breastfeeding her baby. Author: Stanisław Wyspiański / Public domain |

A few women are advised against breastfeeding. This includes women with HIV who may pass HIV to their baby in this way, and women who need to be on medications which could harm their baby via breast milk. However, administration of HIV drugs may allow your child, if you have HIV, to be breastfed with a significantly reduced risk of HIV transmission. Some extremely premature babies may need feeding, initially with special formula or donated breast milk, until your milk comes in, although most will do best with your expressed milk, even initially, when there is only a tiny quantity.

How do I start breastfeeding?

Ideally, when you first start to breastfeed, a trained person should be there to provide skilled help and support, helping you get the baby to latch on and recognise the feeling of milk let-down. A midwife or breastfeeding counsellor can help with this. Getting the first few feeds right can make a huge difference to getting established successfully and can prevent problems such as sore nipples, breast pain and poor milk supply.There won't be very much milk at first and you may feel it isn't enough; however, your baby doesn't need much, and the first milk (colostrum) is very special. It is rich in nutrients and in substances which protect your baby from infection. A newborn baby has a tiny stomach that can hold about a teaspoonful of milk. So, even though there is only a small amount of colostrum, it is enough for the baby in the early days, until the milk supply comes in. Every single feed of colostrum is valuable for both baby and mother's health.

Some women try breastfeeding and give up after a few feeds because it doesn't come as naturally as they expected. We have high expectations of ourselves but, whilst nature gave us the equipment, it takes practice to get it working. Give yourself chance - if you want to breastfeed then you will if you persevere. Be kind to yourself and try not to become anxious about it. It takes time to become an expert.

Breastfeeding can be time-consuming. A newborn baby will feed on demand and this will probably be every 2-3 hours, day and night. As your baby gets older, feeds will be quicker as your milk flows faster. Remember, your breasts produce more milk the more your baby feeds - they will never be empty.

Babies do, generally, get into a routine of feeding but you should still breastfeed on demand, at least in the first few weeks, as this keeps your supply most in tune with your baby's requirements. You feed when your baby seems hungry. This allows for your baby's periods of growth spurts when feeds may need to be more often, and allows for other factors, such as when it is hot and your baby is thirsty.

Your baby receives a more watery foremilk at the start of a breast feed (see image below). This is thirst quenching. As a breast feed continues, the later milk (or hind-milk) is richer in fats. The hind-milk fills your baby up. The hind-milk contains more energy and nutrition needed for your baby to grow and thrive. It is therefore important that the baby finishes on one breast before being offered the second (otherwise your baby would only drink two lots of foremilk).

|

| Two 25ml samples of human breast milk pumped from the same woman, at the same time to illustrate what human breast milk looks like, and how human breast milk can vary. The left hand sample is Foremilk, the first milk coming from a full breast. Foremilk has a higher water content and a lower fat content to satisfy thirst. The right hand sample is Hindmilk, the last milk coming from a nearly empty breast. Hindmilk has a lower water content and a higher fat content to satisfy hunger. As breastmilk is made continuously including during the feed itself, the milk can switch between Foremilk and Hindmilk until the baby has had enough. Credit: Azoreg / CC BY-SA |

How do I get my baby to latch on?

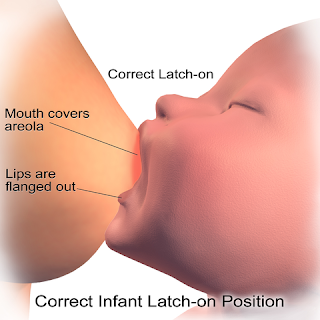

This information is intended as a guide only. Ask a midwife, breastfeeding counsellor or friend/relative whom you trust (and who has successfully breastfed) to show you. Books, magazines and internet resources have good photographs, video and pictures/diagrams to demonstrate positioning and technique.Latching on is the term for getting your baby attached to your breast for feeding. This is the most important thing to get right when starting to breastfeed. Pictures, diagrams and online videos make this easier to understand. Some general points are:

- Hold your baby with their nose opposite your nipple. Your baby needs to get a very big mouthful of breast from underneath the nipple. Placing your baby 'nipple to nose' will allow your baby to reach up and attach well to the breast.

- Let your baby tip their head back, so the top lip brushes against your nipple.

- Wait for your baby to open their mouth wide. As this happens their chin will touch your breast first. Their tongue will be down.

- Quickly bring your baby in to the breast so that a large mouthful of breast can be taken into their mouth.

- There should be more of the darker areola visible above the baby's top lip, than below the bottom lip.

|

| Breastfeeding (Correct Latch-On Position). Credit: BruceBlaus. Blausen.com staff (2014). "Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014". WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436. / CC BY |

- The baby has a large mouthful of breast.

- The baby's chin is firmly touching the breast.

- It doesn't hurt - although the initial sucks are strong.

- The baby's cheeks are rounded throughout sucking.

- There is rhythmic sucking and swallowing, with occasional pauses. There will be cycles of short sucks and also long, deep drawing sucks.

- The baby finishes feeding and comes off the breast on their own.

- If it feels uncomfortable when your baby is latched on, the position may not be quite correct. Use your little finger to break the seal between the baby's mouth and your breast by gently inserting it at the corner of your baby's mouth. Then try again with latching on. This is important to prevent sore, cracked nipples.

What is the let-down reflex?

When your breasts have the let-down reflex, milk is produced from the breast and ejected. This is caused by the chemical (hormone) oxytocin released in the brain. You may feel the let-down reflex as a tightening or tingling through your breasts. It can be almost uncomfortable, and in some women it can be accompanied by a sudden, very intense thirst. If you experience this you should keep a large glass of water within reach when you breastfeed.Just the thought of breastfeeding, or of your baby, or hearing your baby (or other babies) cry, can stimulate milk production and let-down. You may see the milk come in as you are preparing yourself to breastfeed - you may need to wear breast pads inside your bra to catch this milk.

The let-down reflex may be mild in the first few days before your milk 'comes in', but is likely to become more intense later. To begin with, let-down tends to make your breasts more engorged, although after a few months, if you continue to breastfeed, let-down won't produce as much breast swelling.

What is the best position for breastfeeding?

There are lots of different positions for breastfeeding. Key points are:- Keep your baby's head and body in a straight line so that your baby can swallow easily.

- Holding your baby close. Support their neck shoulders and back. The baby should be able to tilt their head back and shouldn't have to stretch to feed.

- Make sure you are comfortable. Breastfeeding can take some time. Sometimes it helps to use a pillow or cushion for support. Your arms or back may end up aching if you are hunched up for a long period of time.

Does breastfeeding hurt?

Sore or painful nipples are one of the main reasons why women who want to breastfeed give up. However, with perseverance and treatment, painful nipples will usually settle down.Nipple pain

Breastfeeding should not be painful, and over time it won't be. However, it's quite common to feel nipple tenderness initially, particularly when your baby first latches on. This is perhaps not surprising - the nipples are a sensitive part of you and a baby's firm little gums have a surprisingly strong grip.Nipple pain is said to be more common in very fair-skinned women, particularly those with red hair. Nipple pain can be caused if your baby does not latch on well. If your baby is held so that just your nipple is just inside their mouth not at the back of their mouth then sore nipples are more likely to develop. Flattened, wedged or white nipples at the end of a feed can suggest your baby hasn't latched on perfectly.

Nipple pain is also more likely to occur if your nipples get chapped or cracked because they spend too much time sitting in damp breast pads. A cracked nipple can easily become infected, and may need antibiotic ointment. If you inspect carefully you may be able to detect a crack yourself. Your midwife or nurse can also check to see if you have a crack or nipple thrush, but nipples can be extremely tender at first even without either of these conditions.

If you develop nipple pain on feeding try a simple nipple ointment between feeds (wiping it off for feeding), and make sure you change breast pads frequently, ideally letting your nipples dry in air.

Nipple thrush

Thrush (candida) of the nipple is a yeast infection that can cause itching and pain, which can be sharp and severe. The nipple may look shiny or flaky and the nipple may be painful through and between feeds rather than just at the beginning.Nipple thrush is more common if you or your baby have recently been treated with antibiotics or steroids. It's also more common if you or your baby have thrush elsewhere on your body. Thrush occurs naturally and harmlessly in the bowel of many people, so may be in your baby's nappy at change time. Candidal nappy rash is also very common.

Nipple thrush can be treated with a cream for candida. Your baby is likely to have candida in his or her mouth if you have nipple thrush, and will need to be given tiny quantities of oral drops at the same time to prevent you reinfecting each other.

Breast pain

Milk let-down and engorgement can feel uncomfortable, but breastfeeding should not be painful. If you develop breast problems whilst breastfeeding, this may be because you have a blocked duct or are developing mastitis. You need to try to identify the problem, and could speak with your doctor, midwife, nurse or breastfeeding counsellor.Nipple shields

For difficult or persistent latch-on problems and nipple pain, the temporary use of a nipple shield can be helpful. Made of soft silicone thin enough not to block nipple stimulation, a nipple shield is worn during breastfeeding. Holes at the tip allow milk to flow to the baby. Nipple shields can be helpful in:- Allowing the baby to pause when feeding without having to repeat latching on.

- Triggering the baby's sucking reflex where nipples are inverted or not pliable enough to be drawn in (over time, the mother’s nipples will become more pliable).

- Persuading a baby who has had bottles and refuses the breast to feed, as the nipple shield feels similar to a bottle nipple.

- Protecting painful or cracked nipples whilst they heal, allowing women who might otherwise stop breastfeeding to continue.

Breast engorgement

A normal full breast can be tender. Breast engorgement can occur on days 2-7 after birth when milk comes in. If milk is not removed by a feeding baby then milk production will soon stop.The best way to minimise pain and engorgement is to give your baby frequent feeds. Some women need some painkillers such as paracetamol for a few days. Some women benefit from expressing some milk by hand to ease any engorgement. Traditionally large outer cabbage leaves have been recommended, worn inside the bra, to ease engorgement, although doctors believe that any cooling item will have the same effect.

What if my baby struggles to suck?

Occasionally your baby may have a problem that makes it difficult for them to latch on or suck properly. The most common cause of this is tongue-tie (ankyloglossia), a problem which means that the tongue is more tightly attached to the bottom of the mouth than normal. Most babies with a tongue-tie have no problems feeding. However, if your baby's tongue-tie does cause feeding problems, it may help to have the tie snipped (divided). This is a safe procedure usually carried out by a specially trained midwife or surgeon.An abnormally shaped mouth, such as a cleft palate, may also affect a baby's ability to suck but breastfeeding is still possible. However, your baby may need to be given expressed milk to begin with and you should be given advice from a specialist breastfeeding counsellor.

How do I know my baby is getting enough milk?

This is a common concern amongst mothers new to breastfeeding. With bottles of formula you can see exactly how much milk has been drunk. Although you can't see the amount of breast milk consumed, there are several other ways to determine if your baby is feeding well:- Watch your baby feeding (see above). You should be able to see sucking, swallowing and full cheeks. When your baby has finished their feed, your breast will feel softer and lighter, especially in the first few weeks.

- By the end of the first week, a breast-fed newborn baby will often produce about six wet nappies and 3-4 dirty nappies per day. Breast-fed baby poo (stools) does not tend to smell and, typically, the stools are very soft and mustard-yellow in colour. (As a breast-fed baby gets older, it can also be normal for them to go up to a week without passing stools.)

- If your baby is alert, usually happy when awake and making wet and dirty nappies, they are usually getting enough breast milk. It is common for breast-fed babies to lose a bit of weight initially but, by 2 weeks of age, they should be starting to gain weight. Occasionally, a baby that is not putting on weight over time may need topping up with expressed breast milk (EBM) or formula. Your midwife, nurse, breastfeeding counsellor or doctor can advise you.

Should I breastfeed on demand?

There are two basic approaches to deciding when your baby should feed, demand-led or scheduled feeding. Breastfeeding on demand means allowing your baby to decide when he wants to feed and how long to feed for. This is recommended by WHO (see above). Scheduled feeding means that you decide when your baby should feed, and sometimes how long for, usually because you are trying to establish a routine.Demand feeding has many advantages:

- It helps establish your breast milk and helps you produce the right amount for your baby, so that your breasts 'settle down' and become less prone to engorgement.

- It makes up for the fact that, unlike bottle-feeding, you can't tell how much milk your baby has taken each time. If they had a smaller feed they may be hungry again sooner.

- It means that your baby can satisfy their hunger when they are hungry, and can increase feed frequency or amount during a growth spurt.

- It also seems to give babies extra benefit in their school performance when they are older (this trial looked at babies being fed on demand for the first four weeks).

Many experts, including WHO, advise feeding on demand until weaning at six months (see above). However, the evidence for this is not very clear. One study looked at over 10,000 babies and concluded that although demand feeding was more tiring for mothers, and that babies gained slightly less weight than with scheduled feeding, babies fed on demand performed better at school several years later. This study looked at demand feeding only up to four weeks, not six months. In 2016 a large review of all evidence, called a Cochrane review, concluded that there was no good quality scientific evidence to choose between demand and scheduled feeding, and recommended that more research is needed.

You will need to decide what you want to do based on how you feel about demand feeding, how easily you can express milk, and the other demands on your life (including work and other children). One pragmatic approach is to feed on demand for the first 6-8 weeks, to fully establish your milk supply. By this stage most babies have established some pattern to their feeding, and you may be able to plan around this without trying formal scheduled feeding. Babies often begin to go through a seven to eight hour night-time period of not feeding once they are around three to four months old. You may be told that this will happen when your baby reaches a certain weight, often quoted at around 5kg, but in fact it relates just as much to your baby's ability to get back to sleep by themselves if they wake in the night.

What is a blocked milk duct?

A blocked milk duct can cause a painful swollen area in a breast, usually in a triangular shape radiating out from the nipple. When you feed your baby, the pain may increase due to the pressure of milk building up behind the blocked duct.Make sure when feeding your baby that your bra or other clothing isn't pressing on your breast and avoid wearing an underwired bra. You may need to massage the area firmly as you feed to encourage flow in the blocked area. It will usually clear within 1-2 days and symptoms will then go. It may clear more quickly by feeding the baby more often from the affected breast as you gently massage the breast. However, in some cases a blocked milk duct becomes infected and develops into mastitis.

What are mastitis and breast abscess?

Mastitis is a painful condition of the breast which becomes red, hot and sore (inflamed). Occasionally, an abscess (collection of pus) may form inside an infected section of breast, causing a firm, red, tender lump. With an abscess, you are likely to feel generally unwell, with flu-like symptoms and a high temperature.How do I express breast milk?

There are many reasons why you might want to express breast milk, including:- Feeding a baby who is too premature to suck.

- Giving your partner chance to bottle-feed your baby.

- Reducing engorgement.

- Leaving breast milk for your baby if you have to leave him or her in someone else's care.

- Helping clear a blocked milk duct.

Hand expressing breast milk

- Cup your breast with one hand then, with your other hand, form a "C" shape with your forefinger and thumb.

- Put the C on the darker area (areola) around your nipple (don't squeeze the nipple itself) and squeeze gentle - this shouldn't hurt.

- Release the pressure, then repeat, building up a rhythm.

- Drops should start to appear, and then your milk usually starts to flow.

- If no drops appear, try moving your finger and thumb slightly, but still avoid the darker area.

- When the flow slows down, move your fingers round to a different section of your breast, and repeat.

- When the flow from one breast has slowed, swap to the other breast. Keep changing breasts until your milk drips very slowly or stops altogether.

Expressing milk with a breast pump

- Follow the instructions on the pump, which will have a suction cup which you place over the nipple. These sometimes come in different sizes.

- Different pumps suit different women, so if you can borrow one first this may be helpful.

- Manual pumps are cheaper but tend to be slower, and your pumping hand can get quite tired.

- You may be able to hire or borrow an electric pump.

- Always make sure that the pump and container are clean and sterilised before you use them.

Can I breastfeed with twins or more?

You can breastfeed as many babies as you have, and your body will produce milk to meet the demand. However, breastfeeding twins is definitely very demanding and you may need practical help in setting up your feeding sessions, particularly if you like to feed both of your twins at once.Many women fully breastfeed twins. Twins can be fed separately, together, or in a mixture of both. Some women use a large, v-shaped cushion to support their babies whilst they feed, and describe using a 'kitten hold' (moving the baby with their bunched babygrow) to help position them.

Can I breastfeed if my baby is ill?

If your baby is unwell - for example, having diarrhoea - you should continue to breastfeed. (In some circumstances, you might be advised by a medical professional to give extra fluids or oral rehydration therapy. However, for mild illnesses, breast milk alone is fine.)What is jaundice?

Jaundice is a very common condition in young babies. If your baby has jaundice, he or she develops yellowing of the whites of the eyes and the skin. It has a number of causes.Physiological jaundice

About 6 in 10 full-term babies and 8 in 10 premature babies are jaundiced. It happens due to changes in the baby's blood circulation and liver. It is not present at birth but starts at 2-3 days of age, in a baby who remains well and continues to feed and cry normally. Physiological jaundice is usually settling by the end of the first week and gone by about day 10.Breast milk jaundice

Breast milk jaundice lasts up to six weeks (occasionally longer) but, again, is not present immediately at birth. Babies with breast milk jaundice often do not need any treatment. Jaundice can be worse if a baby is lacking in fluid (dehydrated), so it is important that they are feeding well.Jaundice at birth

Jaundice that is present at birth or within the first 24 hours of life is more worrying, as it usually has an underlying medical cause. Your baby will probably need further tests if they develop jaundice so early on. Some babies need treatment - for example, with ultraviolet (UV) light treatment (phototherapy). The exact treatment depends on the cause.Is it worth breastfeeding just for a few days?

Yes - even if you only breastfeed for a short period of time, there are huge benefits. In particular, you will have given your baby valuable antibodies which will last for several months. If possible, try to continue breastfeeding for six months, even if you have to go back to work. It is possible to express and store breast milk so that the person caring for your baby when you are at work can give it to them. This can be slow at first, but once breastfeeding is properly established (usually 4-6 weeks of age), it becomes easier.Breast milk can be expressed by hand, with a manual breast pump or with an electric breast pump. You can keep breast milk, in suitable sterile containers or bags, in a fridge for up to five days at 4°C or lower. It can even be frozen (up to six months at minus 18°C).

Doesn't breastfeeding prevent the father from sharing in our baby's care?

There are many ways for fathers to be involved with their baby - holding, bathing, playing and helping with caring for the baby in many other ways. However, you can express breast milk and your partner can give it to your baby via a bottle, allowing them to share more completely in the experience. For the easiest experience, wait until your baby is 4-6 weeks before doing this, so that your breast milk supply has settled into a pattern and the baby has fully learned to feed from you. However, you can do it earlier than this if you wish to. You can read more about persuading breast-fed babies to bottle-feed.Your partner's support is invaluable when you are breastfeeding. A mother is far more likely to persevere with breastfeeding if she has a supportive partner, and she is also more likely to have a positive experience.

Can I breastfeed in public?

This has been a contentious issue in recent years, with stories of women being asked not to breastfeed in public, or being banished to restaurant lavatories to do so.Women, whilst agreeing that those who want to breastfeed in public should be able to do so, have different feelings about how they feel about feeding in public. Many breastfeed wherever they wish, as openly as they wish, and answer criticism boldly. Others, understandably, find criticism upsetting and distressing, and find private places in order to avoid confrontation. Some avoid going out at all, as they don't want to have to feed in public.

Whilst there are some parts of the world where it would be, culturally, extremely difficult for women to breastfeed in the presence of men, in the Western world it is entirely possible to breastfeed discretely, under a muslin cloth or nappy, if you wish to be private. You should of course never be banished from any public space for feeding your baby. One day, perhaps, we will live in a world where people never regard breastfeeding as odd or indecent. In the meantime, you need to do what's right for you.

Do I need a special diet when breastfeeding?

A normal healthy balanced diet is advised for breastfeeding mothers. Breastfeeding can make you thirsty, so make sure you drink plenty of fluids, including water. You don't need to drink milk in order to make milk (although it is a good source of calcium).- Breastfeeding uses up approximately 500 calories per day, so it can help you lose weight. You may find that it makes you hungry, so try to eat healthy snacks that release energy slowly (like nuts, bananas, dried fruit, etc).

- A vitamin D supplement is recommended for all breastfeeding and pregnant women. There are a number of multivitamin supplements for pregnancy and breastfeeding, that contain vitamin D, or you can take a calcium/vitamin D tablet. 400 units (10 micrograms) per day are advised.

- Your baby may need to receive drops containing vitamin D from 1 month of age if you have not taken vitamin D supplements throughout your pregnancy. If you did take supplements when you were pregnant then your baby should start taking vitamin D drops when they are 6 months old.

- Certain foods may affect the taste of your breast milk and your baby may notice this and might seem put off. Foods which have been implicated include garlic, aromatic spices and citrus fruits. They will usually have only a temporary effect on the taste of your milk.

Can I breastfeed if I am unwell?

For most mild illnesses, such as diarrhoea, being sick (vomiting), coughs and colds, it is important to continue to breastfeed, if you are able. Your milk will help to protect your baby from the same illness, or at least make it milder because of the antibodies that you make that are passed to your baby through breast milk. Remember your baby will have been exposed to any illness you have, before you know you are unwell.You may need to drink extra fluids, especially if you have diarrhoea or vomiting. Avoid coughing and sneezing over your baby (whether breastfeeding or not).

It is perfectly safe to breastfeed, and poses no risk to your baby, if you have a long-term (chronic) health problem. This includes illnesses such as diabetes, asthma, arthritis, heart disease, etc. It is very rare that you would be advised by a medical professional to discontinue breastfeeding due to your medical condition.

If you have a chronic illness or infection and are worried about whether you should breastfeed your baby, discuss this with your doctor. Some medications should not be taken when breastfeeding (see below).

Can I breastfeed if I have HIV?

Without preventative interventions, about one third of babies born to mothers infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) - the virus that causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) - also contract the disease.Mothers who are treated with antiretroviral medicines through their pregnancy have a less than 1 in 100 chance of passing the virus to their baby. If the mothers are also well, with a low or undetectable virus count, that transfer risk reduces to 1 in 1,000. Babies of HIV-positive mothers are given preventative HIV medicine at birth. However it is possible for babies to acquire HIV through breastfeeding, and the risk of doing so is 1-4 in 20.

Because of this, in countries where formula and safe water are easily obtained, HIV-positive mothers are advised not to breastfeed.

In developing countries, the risk of HIV transmission with breastfeeding has to be balanced against the risks to the baby of not breastfeeding. In these countries, women cannot safely formula feed, due to issues with supply and cost of formula, availability of clean water and facilities for sterilisation of equipment. Breastfeeding is the only realistic option for these mothers. So, in developing countries, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that when HIV-infected mothers breastfeed, they should receive treatment for HIV and also breastfeed.

Can I breastfeed if I have hepatitis B?

If you have hepatitis B infection, you should still breastfeed your baby. It is vitally important that your newborn baby should be immunised against hepatitis B at birth. The hepatitis B vaccine and hepatitis B immunoglobulin (an immune system protein that fights infection), given within twelve hours of life, give the baby a 95% chance of being protected against hepatitis B infection.Does any prescribed medication affect breastfeeding?

Most medicines pass into breast milk. Usually this is in very small quantities - amounts too small generally to be considered harmful. It is safe to breastfeed with most prescribed medications. However, there are some exceptions, and the age of your baby is also important. If you have a low-birth-weight or premature baby, the amount of medication in the breast milk could pose more risk.Many medications are unlicensed in breastfeeding mothers. This means that the manufacturers have not undertaken research into their safety in breastfeeding. This sort of research often can't be done for ethical reasons, as breastfeeding women couldn't be given medicines experimentally to find out if these would harm their babies. However, if a medication is also available in a formulation for children, it is likely to be safe in the tinier quantities present in a mother's breast milk.

- The value of continued breastfeeding generally outweighs the risk of a small amount of medication being passed in a mother's milk to the baby. Stopping breastfeeding for a few days can be enough to impair breast milk production.

- If it is felt that it would be safer for the baby not to take in (ingest) breast milk that might contain medication taken by the mother, breast milk should ideally be expressed and discarded until the medication is no longer being taken, so that the supply is maintained.

- Simple painkillers such as paracetamol and ibuprofen, levothyroxine (for an underactive thyroid gland), inhalers for asthma, and most common antibiotic medicines, are safe in breastfeeding mothers.

- The combined oral contraceptive (COC) pill - also known as 'the Pill' - may reduce your milk supply, so is not advised during breastfeeding until your baby is 6 weeks old, when your supply is usually fully established..

- Progestogen-only contraceptives (including the progestogen-only pill - 'mini-pill') do not affect milk volume, and barrier (for example, condoms) methods are fine when breastfeeding.

- Some medicines, such as chemotherapy agents, powerful painkillers (opiates), anaesthetics and strong anti-thyroid drugs, pass into breast milk in high enough quantities to mean that you should not breastfeed whilst taking them.

- If your doctor knows you are breastfeeding then, where there is a choice of medicines that you can be prescribed, he/she will choose one that is believed to be safe when breastfeeding.

Can I use recreational drugs when breastfeeding?

Recreational drugs should NEVER be used by breastfeeding mothers. They impair your ability to feed and care for your baby safely, and may affect your conscious level so that you, for example, fall asleep when caring for your baby or, worse still, fall asleep on your baby.These drugs can also cause serious harm directly to the baby. If you abuse opiates in particular, you may be very tolerant to them, but your baby will not be and could die.

If you abuse these drugs, do not breastfeed your baby, and seek medical help to come off them. A methadone maintenance programme may be offered to help stabilise you to help you do so, although methadone is present in breast milk and will sedate your baby, so you will usually be advised not to breastfeed. Heroin, cocaine, 'angel dust' (PCP), and hallucinogens (such as LSD) are amongst the most dangerous substances; however, cannabis, amfetamines and other synthetic drugs of abuse also pose considerable risks.

Can I smoke when breastfeeding?

Nicotine (in tobacco) is also a drug. Passive smoking is associated with an increased risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and with increased rates of respiratory illnesses, including long-term problems such as asthma.If you smoke, you should try to give up, not only for your baby's health but for your own as well. Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) may help you. Although NRT is not licensed for use in breastfeeding mothers, the amount of nicotine your baby is exposed to is considerably less than with smoking and, importantly, your baby is not exposed to all of the other poisonous (toxic) chemicals in cigarette smoke.

Can I drink alcohol if breastfeeding?

Ideally, keep alcohol consumption to a minimum when breastfeeding. Alcohol passes into breast milk freely and levels in breast milk are similar to those in the mother's bloodstream. Long-term exposure of a breast-fed baby to more than two units of alcohol per day can have a negative effect on a baby's development.Very occasional social drinking will not cause harm to your baby, so long as you are sensible and careful, perhaps having a glass of wine over a whole evening so that your blood alcohol levels never rise very much.

Who can advise me on my worries about breastfeeding?

If you have any worries or concerns about breastfeeding then a nurse, midwife, breastfeeding counsellor or doctor will be happy to help. Most difficulties can be overcome.There are a number of organisations which can also offer help and advice. Often, there is a local breastfeeding workshop or clinic, where you can attend with your baby for professional and practical help.

Can I breastfeed whilst pregnant?

It is entirely possible to breastfeed whilst pregnant. It is also possible to tandem feed, which means breast-feeding a baby and their older sibling. Some women find that their breastfeeding baby starts to reject the milk and seems to be self-weaning in late pregnancy, which may be because the taste of the milk is changing towards colostrum, but this is not always the case.When should I stop breastfeeding?

Breastfeeding for a full six months, until weaning, is ideal as it gives you and your baby the full health benefits of breastfeeding.Beyond this, deciding when to stop breastfeeding is usually a personal choice. Returning to work, your baby becoming more of a toddler (with teeth) and further pregnancies may play a role in this decision, and some women have a sense of 'wanting their bodies back'. There is no right or wrong.

In general, to stop breastfeeding you reduce the number of breast feeds, replacing them with formula feeds (in children aged under 1 year) or normal milk (in older children). Often, the last feed of the day before bed is the final feed to be dropped.

Although this leaflet is intended to promote breastfeeding and its benefits to mother and child, some women will choose to formula-feed their baby for personal, physical or health reasons. If you choose to formula-feed, you should not feel guilty or that you have failed because you have not or could not breastfeed. You have already done a great deal by carrying your baby through a successful pregnancy. Breastfeeding is just one of many other things you can do to raise your baby healthy and happy. Formula feeds provide excellent nutrition for your baby. Once you have decided what to do it is important that those close to you support your decisions.

Can I go back to breastfeeding if I have stopped?

This can take perseverance, but you can. Breastfeeding can be established for months after birth, even if you have initially bottle-fed, and it is even possible to establish breastfeeding in a woman who has not been pregnant (for example, after adoption).Reference(s)

1). World Health Organization: Breastfeeding.

2). World Health Organization: Childhood overweight and obesity.

3). UNICEF: Breastfeeding: A smart investment.

4). UNICEF: The Baby Friendly Initiative.

5). GOV.UK: Childhood obesity: a plan for action.

4). UK Dept of Health: HIV and Infant feeding.

5). F McAndrew et al; Infant Feeding Survey 2010, Health and Social Care Information Centre, November 2012

6). Silano M, Agostoni C, Sanz Y, et al; Infant feeding and risk of developing celiac disease: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016 Jan 256(1):e009163. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009163.

10). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (February 2016): Patterns of breastfeeding, according to the baby or according to the clock.

11). Iacovou M, Sevilla A; Infant feeding: the effects of scheduled vs. on-demand feeding on mothers' wellbeing and children's cognitive development. Eur J Public Health. 2013 Feb23(1):13-9. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks012. Epub 2012 Mar 14.

12). Crepinsek MA, Crowe L, Michener K, et al; Interventions for preventing mastitis after childbirth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Oct 1710:CD007239. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007239.pub3.

13). NICE CKS (August 2015): Mastitis and breast abscess.

14). Brown A, Jones SW, Rowan H; Baby-Led Weaning: The Evidence to Date. Curr Nutr Rep. 20176(2):148-156. doi: 10.1007/s13668-017-0201-2. Epub 2017 Apr 29.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Got something to say? We appreciate your comments: